Provincial government boundaries came into effect on 17 January 1853. Over time the number of provinces increased to ten

Map courtesy of Te Ara, The Encyclopedia of New Zealand

Two recent work-related mix-ups around Auckland Anniversary Day got me wondering about the when and why of provincial anniversaries. A quick search online revealed their relevance is increasingly debated and calls for consolidation, or even cancellation, are frequent. One of the most persistent arguments is that regions, like Waikato, should have their own celebration. Seemingly anniversaries being determined by a system of provincial government established in 1852 and abolished in 1875 is at best antiquated, and at worst, a vestige of colonialism. [i]

William Hobson, Oil portrait by James Ingram McDonald

Courtesy of Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Matauranga o Aotearoa

Six regions currently celebrate Auckland Anniversary - Waikato, Auckland, Coromandel, Bay of Plenty, Northland, Gisborne, and parts of Manawatū-Whanganui. The day carries the additional historical significance of being New Zealand’s first public holiday. The commemoration date of 29 January marks the arrival of William Hobson in the Bay of Islands in 1840 and was gazetted in 1842:

Saturday, the 29th instant, being the SECOND ANNIVERSARY of the establishment of the Colony, His Excellency the Governor has been pleased to direct that day to be held as a GENERAL HOLIDAY on which occasion the Public Offices will be closed.[ii]

Hobson would later state that 30 January was the day the Union Jack was hoisted up the Herald’s flagpole at Kororāreka (Russell) and British Sovereignty over New Zealand was proclaimed. As a result, there was some fluidity around the date of the anniversary. At the end of the 1800s and the turn of the 1900s, the Bay of Plenty Times regularly printed advertising which used either date.

With ‘Mondayisation’

the date we observe the holiday is different each year. Indeed, in 2027

Auckland Anniversary won’t even be in January, the Monday falling on 1

February.[iii] Not

that this will be the first time it’s been held in February. In 1901 the death

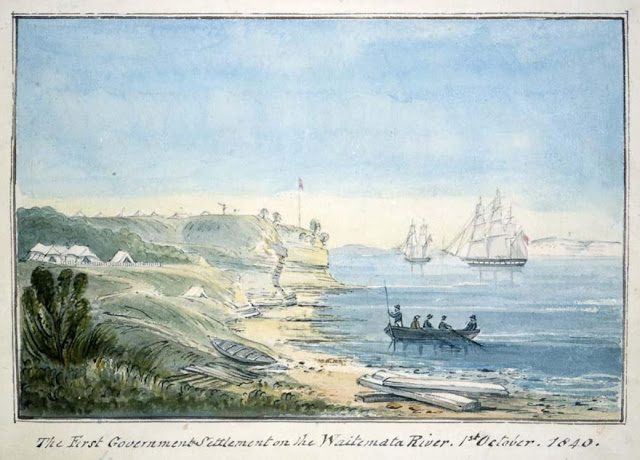

of Queen Victoria necessitated the postponement of the celebration.[iv] The campsite of the advance party sent to establish the newly founded city of Auckland, September 1840

Courtesy of Alexander Turnbull Library, National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Matauranga o Aotearoa, Ref. E-216-f-115

Last year, in an additional twist to the date debate, Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei Trust called for the holiday to be moved to 18 September – the day Ngāti Whātua chief, Āpihai Te Kawau, gifted Hobson 3000 acres to establish the settlement of Auckland.[v] According to the trust this was the “true birth of the city”.[vi] While this seems a valid point for Auckland, those of us in the regions might be left wondering if it is indeed time to go our separate ways. However, it might be a case to be careful what we wish for as how can the Bay of Plenty – as diverse as it is – find a date of significance to all?

[i] Why NZ’s outdated regional anniversaries should be ditched | The Spinoff Auckland Anniversary 2024: Waikato community leaders supportive of own celebration - NZ Herald

[ii] The New Zealand Government Gazette, 26 January 1842, (Volume 2, 4th edition)

[iii] For those reading this blog in the future this year’s date is 27 January 2025.